CAMEROUN ELECTIONS AND THE BLAME GAME

Anglophones blaming each other instead of confronting the real cause of their problems are like “5 and 6.” Elections that the CPDM has rigged for over 43 years suddenly seem to have gone wrong because Ambazonians—who do not even recognise the authority of Cameroun over their territory—declared a lockdown.

Before you jump on this, let me be clear: while I support the boycott, I do not subscribe to prolonged lockdowns that hurt the very people whose welfare should be prioritised.

That said, Mimi Mefo and her kind have deliberately chosen not to see beyond the lockdown. They refuse to question how Momo suddenly has a larger population than Mezam, or how the CPDM shamelessly concocted figures in the South Region where there was no lockdown at all. Instead, they blame Ambazonians for the rigging—as though there have ever been free and fair elections in Cameroun, from the “Oui” referendum of 1972 to date.

I don’t blame them, though, for two reasons:

-

In a conflict situation like ours, Ambazonians have always been blamed for everything negative—even when they have shown greater respect for the rules of war than La République. They are accused even when they know nothing (not that there haven’t been violations on their part). As a non-state actor, it is easier to blame them without facing prosecution.

-

Criticising separatists has become the platform on which many have built their fame—and, to some extent, their fortune—in this age of paid social media engagement. So, it becomes easy to keep hammering on the source of one’s income.

I personally believe that the key issues, as Tassang clearly stated on January 7th, 2017, are historical and communal, far deeper than elections or changes of face in La République. Those talking down on revolutionaries in Southern Cameroons have not studied history; they do not understand that there are no perfect revolutions—not even the planned ones. How much more one that rose spontaneously, whose level-headed leadership was betrayed and imprisoned, leaving others to do what they can with what remains.

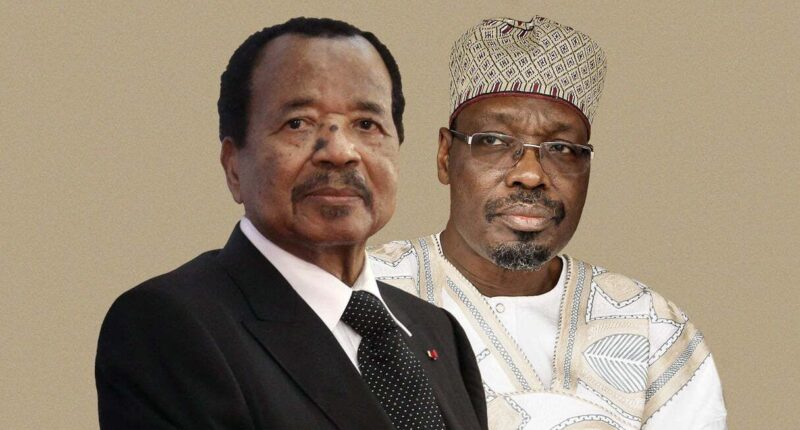

It must be made clear: while elections in La République and a possible change of Paul Biya may (I insist on may) play a role in resolving the Southern Cameroons conflict, it is not for Southern Cameroonians—who question La République’s authority over their land—to participate in any election that implies acceptance of that authority. Those who voted, voted. Those who did not, did not. Let the eagle perch, and let the hawk perch.

Of course, there are those who still believe Cameroun can be reformed to treat Southern Cameroons justly—and others who believe it is impossible to expect equality and justice from La République. Whatever your position, pursue it without tearing down others doing the same.

Let me state this clearly: the people of Southern Cameroons may be quiet, but they are not blind. The day will come when they will speak, and then we shall see who has truly stood with the people—and who has not.

The Southern Cameroons conflict has revealed much to me personally over the years. I have seen men who once hardened the positions at the start of the crisis later take up offices in La République’s institutions. I have seen people who once prophesied freedom become victims of their own words—moving from “Free Southern Cameroons” to “Two-State Federation,” to “Ten-State Federation,” to “a better president than Biya.”

I have seen people we fought to free from La République’s detention turn against us while enjoying asylum gained through the very struggle they now mock. I have seen individuals I once believed were true to the cause of justice change colours like chameleons at the sight of money—whether from citizen donations or bribes from La République.

Yet, one thing has remained constant: the quest for freedom by the people of Southern Cameroons.

Perhaps it pleased God that from the very beginning, everyone knew what we were fighting and dying for—so that when the time comes, no one can sell us out and claim the issue is resolved. Is it then surprising that the crisis has remained in focus despite all the errors and sabotage?

The so-called “Anglophone Crisis,” or what I prefer to call the Southern Cameroons’ Quest for Freedom, goes far beyond elections—though it may be influenced by them in La République. We must never trivialise a sovereign people’s struggle by reducing it to elections organised by the colonial power.

Do I like elections? Yes.

Do I want Paul Biya gone from La République? Eagerly.

Do I support rigging? Not at all.

While we pray, hope, and work for a new face in La République, we must never lose focus on what brought everyone out on 22 September 2017—and that, certainly, was not about changing faces in La République, even if that might help.

Good morning.

MBERAMBO.